Lessons Learned

By Denice Rackley

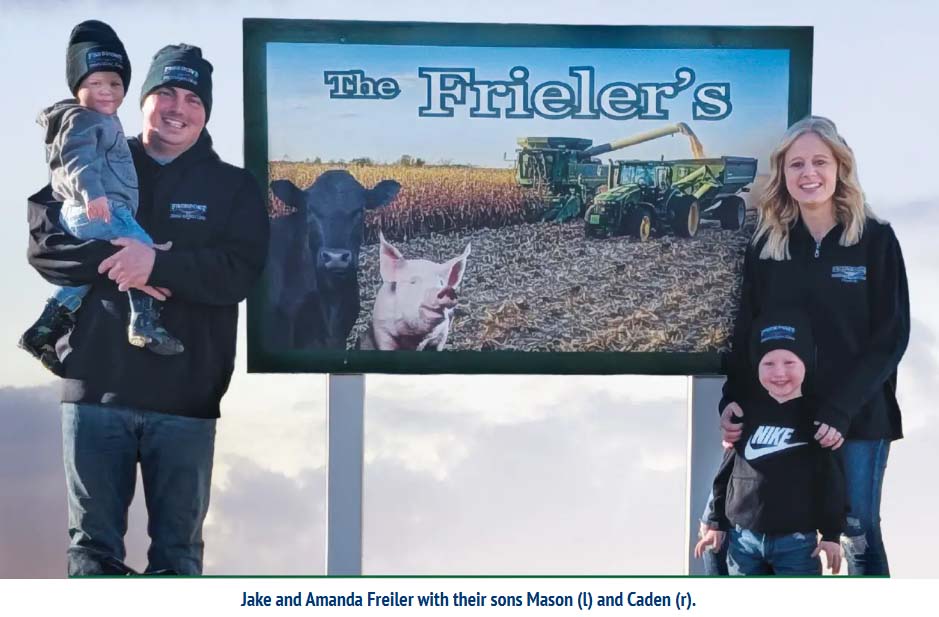

Livestock has been a staple on the J&A Frieler Farm, LLC in Melrose, Minnesota, since the start. This land, which evolved into a small farm with a diverse mix of crops and livestock, has supported the Frieler family for over 100 years.

The towns surrounding the farm and the agriculture industry itself have weathered many changes in that time. Rural populations exploded and then withered as farmers embraced machinery, new products and growing techniques to increase production. As much as we try to avoid change, it is inevitable. Now, J&A Frieler Farm is undergoing another change that Jake Frieler hopes will cement the farm’s future.

Transitions

Buying the farm from his parents this past year, Jake and his wife Amanda, along with their boys Caden, three, and Mason, just one and a half, moved into the farmhouse from town. “I am the third generation to manage the farm,” Jake said.

Growing up on the farm, working alongside his dad, he and his brother were the hired help, minus the pay of course. “Hogs have been our bread and butter for as long as I can remember,” Frieler remarked.

It’s no wonder that raising hogs is a staple of the Frieler farm. After all, Minnesota ranks third in the number of pigs raised after Iowa and North Carolina. The Frielers grow a Landrace-Yorkshire cross, selling good producing gilts as breeding stock. “Gilts have been shipped to operations within Minnesota and out of state to Iowa, Illinois and Nebraska,” Frieler said.

While he is proud of the breeding stock he raises, it is the farrow-to-finish operation that demands his time. “We have had 750 piglets born in the last two days.” With state-of-the-art biosecurity in place, simply showering in and out of each barn can be time-consuming, let alone ensuring that the new additions are well cared for.

Pigs far outnumber the cattle on the farm, but Frieler might enjoy his time with cattle more. His dad had always raised a few calves in hutches, but Frieler has taken calf raising to new heights.

Turning Bottle Calves Into Fat Cattle

In Minnesota, weather presents significant challenges to livestock producers. Quite possibly the harsh winters and the thousands of crop fields are responsible for Minnesota’s 3,000 pig farms marketing 16.9 million hogs in 2022. If multiple heated buildings and automated technology work to raise pigs, then why not apply those methods to growing calves?

Using a four-barn progression to take bottle calves all the way to fat, Frieler has the system down to a science. “We bring in 54 Holstein beef cross calves every four weeks,” Frieler noted. Calves, two to six days old, are housed in a heated calf barn with six automatic ID TEC calf feeders. This barn has six pens, each holding up to 18 calves. Frieler sorts calves into pens by weight and then calibrates the machines in each pen accordingly. The auto feeder dispenses milk to the calves up to nine times daily, recording the amount each calf receives.

“The auto-feeders alert us when a calf isn’t eating, then we investigate. Sometimes, it’s as simple as the calf jumped into another pen. Sometimes they are not feeling well, but the automation enables us to catch things quickly,” he noted. Each day, the feeders are cleaned, milk replacer added, and calibrations adjusted if needed. Pens are cleaned and bedded with new straw every three days. The calves also have access to feed and corn mixed with a commercial pellet, which enables weaning to go more smoothly.

Stickler For Cleanliness, Frieler believes It Has Direct Impact On Health

After about 56 days on milk, the calves are transferred to barn number two. In this heated barn, augers transfer feed into bunks at each straw bedded pen. Calves weigh about 160 to 180 pounds when they enter barn two and head to the next barn weighing 350 to 400 lbs after 56 days on feed.

Barn three has four pens and curtains and is bedded with corn stalks. “We feed in there for around 120 days,” Frieler said. With calves weighing about 675 pounds, they spend the remainder of the time in the finishing barn, hanging out, eating and getting fat. The fourth barn is set up a bit differently. “Cattle are fed a total mixed ration with straw added to the protein pellet and corn. The floor is Easy Fix rubber coated slats which gives the calves some cushion and grip,” Frieler noted. Slat flooring is beneficial since it allows urine and manure to fall through, but the slats are tough on the cattle. “The floor coating really improves comfort and health. We don’t have feet or knee issues that are common in cattle on concrete.”

The protein content of the commercial pellets and corn/pellet ratio fed is adjusted as the calves grow and transition to the next barn. “We begin with a herd builder pellet as a baby calf, then move to a developer pellet and lastly transition to a finisher pellet in the slat barn.” Cattle are marketed around 1500 lbs with the assistance of National Farmers Steve Eveslage. “Steve helps us with hauling hogs and cattle. We rely on his expertise in marketing and shipping. And we always use Freeport Trucking,” Frieler said.

To ensure the calves grade well and move through the barns as quickly and efficiently as possible, implants are used. “Hands down, implanting makes a difference,” Frieler remarked, but the implanting protocol differs with the breed of calves he is fattening. The Holstein beef cross calves are given an implant three different times through the growing process. The first implant occurs once the calves are weaned, then again when they weigh approximately 450 lbs, with the last implant given when the calves reach around 1,000 lbs.

Crop Fields Provide More Than Corn

Crop fields are an integral part of the Frieler operation. Not only does it take quite a bit of corn to finish livestock, but all those hogs and calves produce quite a bit of manure. The Frieler’s crop acres provide the space to spread the manure and produce most of the needed feed and bedding.

Managing crops and livestock is more than a full-time job, but with the help of his dad, Tom, and employee, Angel, it all gets done eventually. During the fall harvest, Frieler Farms does have additional hired hands to help them through the busy season.

Challenges and the Future

Frieler’s most significant challenge isn’t acres, feed, or weather; it is sourcing the needed numbers of good cross calves. While the number of dairies is shrinking, more people are feeding cross calves. With current cattle markets, there are also dairies that maintain ownership and feed out their calves, he noted. “We are looking further afield to source calves, and exploring other crosses.” There will always be change and challenges to overcome, but Frieler is committed to finding workarounds.

Jake Frieler’s life has revolved around the farm. “I did think about getting a regular job and going to college, but one summer working construction changed all that.” Not enjoying his days off the farm like he thought he would, Frieler is glad to have the opportunity to raise his family on generational land where his roots are firmly planted.