Capitalizing On Change Breitenmoser

Dairy Milks 460 Cows, Farms 1400 Acres

By Denice Rackley

Alongside numerous small family dairies that dotted the rural Wisconsin landscape, the Breitenmosers made the long journey from Switzerland to America wanting a better life. Hans Sr. and Margrit Breitenmoser arrived in 1968 with the hope that hard work would result in a prosperous farm and happy life.

Beginning with 25 head of commercial Holsteins, that dream began to materialize. Hans Sr. and Margrit poured their lives into Breitenmoser Family Farm.

Fast forward over half a century and Holsteins still dot the same landscape. Since the day he entered the world, Hans Junior has called this farm home. Continuing the family dairy with his wife, Katie, and five children – the dream hasn’t really changed, but the dairy industry sure has.

Traditional Dairying With Eyes On the Future

“We milk around 460 cows, raise our own replacements and farm about 1400 acres,” said Hans Breitenmoser Junior. With a deep connection to this life and land evident in his voice Breitenmoser explained, “Mom lives on the farm and helps out, Dad is buried in the cemetery just up the road.”

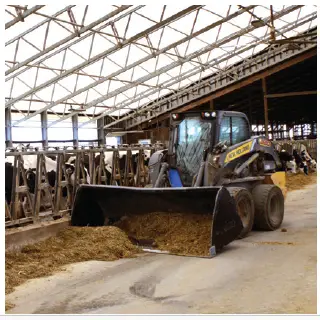

The cows are milked three times daily in a double ten parabone parlor that was moved to the farm and installed after a fire in 2014. The replacements and dry cows are rotationally grazed while the lactating cows are fed a total mixed ration in a sand bedded free stall barn.

The top producing cows are artificially inseminated with sexed Holstein semen to provide the 17 females per month needed to maintain herd size. “We have been using sexed semen for about 19 years. This enables us to pursue the genetics we want and concentrate our resources on raising exceptional replacements,” Hans explained.

The replacements start out in hutches, then move to a bedded pack barn. The bedding is composted and sold to a neighbor who utilizes it in a vegetable production business.

The remaining cows are artificially inseminated with Angus semen to produce valuable beef cross calves. These calves are sold at a local sale barn at three to seven days old. Currently, cross calves are bringing quite a bit more than straight dairy calves, averaging around $1,100.00 each.

“Our calf check is a byproduct of milk production, and it definitely helps with the bottom line. Selling high quality Angus cross wet calves means we are not assuming much risk while providing opportunities for other producers.”

Poised for Change

The Breitenmosers have emphasized A2/A2 genetics for more than 15 years. Some individuals find A2 milk much easier to digest which could allow for a wider percentage of the population to drink milk and consume other dairy products.

Most commercially available milk is a combination of A1 and A2 proteins, but A2A2 milk is from cows that only have the A2 beta-casein protein. If a market develops locally for A2 milk, Breitenmoser is poised to benefit from potentially higher premiums.

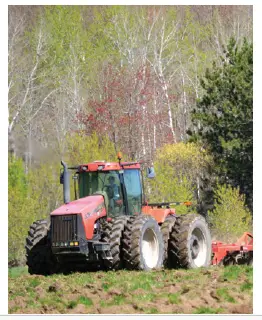

Raising corn for grain and silage as well as forage oats and a mixture of grasses, clover and alfalfa, most of the needed feed is produced on the farm. But Breitenmoser ventures off the beaten path by raising non-GMO crops. “We began raising non genetically modified crops as a way to capitalize on that milk market,” he noted.

“Actually, that is how we hooked up with NFO, as they were looking for non-GMO milk. Even though the nearby processing plant stopped sourcing non-GMO milk, we have continued raising non-GMO crops. And we remain with National Farmers because the organization is committed to assisting family farmers.”

In recent years, many studies have focused on adding specific products to cattle feed that reduces methane emissions. Breitenmoser adds an essential oil based ionophore supplement, Agolin, that improves rumen efficiency while reducing methane production.

Capitalizing on energy from the sun, solar panels have been used to help power the farm since 2012. Partnering with Wisconsin Farmers Union and Legacy Solar Cooperative, Breitenmoser powers 100 percent of their heifer free stall barn and his family’s home during the summer months.

The Future of Dairying

Concern about the dairy industry is top of mind for many dairy families. Wisconsin might be known as a dairy powerhouse and the cheese state, but the number of dairy farmers leaving the industry is staggering.

In 1899, 90 percent of Wisconsin farms raised dairy cows, by 1915 the state was producing more cheese and butter than any other in the U.S. Today, the Wisconsin Dairy Organization reports that Wisconsin, while it ranks second among states in milk production, only has about 5,500 dairy farms. Compare this to 125,000 plus farms in 1930 and 64,000 in 1970. The trend is alarming, especially knowing the same thing is happening across the country.

Labor, tariffs, vertical integration and oversupply are front of mind for Breitenmoser. Shipping five semi loads of milk a week from milking 400 lactating cows three times daily requires experienced, dedicated workers. “Most of our workforce is from Mexico. I hesitated hiring people who don’t speak English as their first language for a long time, but others were making it work and eventually there weren’t other options,” he said.

“We have found ways to overcome the language barrier and as a result are blessed to work with wonderful, hardworking individuals.”

Possibly Breitenmoser has a soft spot for others who come to America looking for a better life. But, he is also a realist and noted, “the dairy couldn’t function without them.” He continued, “There is no logic in demonizing ag workers, of any nationality. The current deportation policies make no sense.”

Tariffs present another source of concern that Breitenmoser believes will negatively impact dairy and the ag economy in general. And then there is the consistent loss of family dairies while corporate owned dairies are getting larger.

“The loss of small farms is felt throughout the community,” he said. Local infrastructure is impacted; larger dairies mean more semis and stress on roads. Churches, schools, local businesses suffer. Communities and society in general is altered,” Hans emphasized.

Survival Is Tied To Choices

If family dairies are going to survive, Breitenmoser believes, milk supply needs to be managed. And management needs to come from producers themselves. “We know the ‘get bigger and produce more philosophy’ doesn’t work,” he said. “It’s time for self-discipline that matches supply with demand so that everyone can prosper.”

Like the National Farmers Organization, Hans Breitenmoser is a vocal advocate for family dairy farmers and the numerous benefits that family farms bring to communities.

Banding together with producers like Breitenmoser, who is a force within his community, we can achieve our mission to help sustain our farm families throughout the country.